One City, By Bike: Huge Opportunities for NYC Cycling in the de Blasio Era

Jon Orcutt was NYC DOT’s policy director from 2007 to 2014. He developed DOT’s post-PlaNYC strategic plan, Sustainable Streets, oversaw creation of the Citi Bike program, and produced the de Blasio administration’s Vision Zero Action Plan. In this five-part series, he looks at today’s opportunities to build on the breakthroughs in NYC cycling made during the Bloomberg administration.

Part 1 – What’s Next for New York City Cycling Policy?

Bike transportation in New York City unquestionably saw historic progress during the second half of the Bloomberg administration. For the first time, city government treated cycling as a serious mode of transportation and continually achieved new milestones: a bigger bike network, safer street designs, higher cycling levels, and a network of bike-share stations that received massive usage. NYC DOT, City Hall, and city cyclists endured and moved past the “bikelash.” But even after smashing so many barriers, cycling in New York is still relatively underdeveloped, with gigantic opportunities for growth ahead.

2014 has not been without progress: This year, new bike networks began to take shape in Long Island City and East New York. New lanes on Hudson and Lafayette Streets added to Manhattan’s set of protected bikeways. A key Queens-Brooklyn bottleneck will be uncorked with the pending Pulaski Bridge dedicated bike lane. And NYC DOT has spent the year to date renegotiating the Citi Bike operating agreement to give the system stronger management and the resources needed for technological improvement and expansion.

But it’s important to recognize that what we’re seeing on the streets in 2014 are projects developed under the Bloomberg administration and Janette Sadik-Khan’s leadership at NYC DOT. DOT’s annual street improvement program takes shape during the fall and winter: Implementation begins in late winter and spring when weather becomes warm enough to resurface and repaint city streets. The 2015 program will be the first shaped by Mayor de Blasio’s administration and new DOT leadership. Will it have a strong bike lane component, and where are the additions to the bike network likely to be?

De Blasio’s campaign material promised significant progress, calling cycling a mainstream means of travel in the city. He stated that his administration would achieve a 6 percent bike mode share by 2020 by expanding bike lanes and bringing bike-share to the boroughs. Putting aside the problem of measuring mode share, the mayor was right to recognize that there are huge opportunities to take cycling in New York to new levels — the city can still achieve manifold increases over cycling’s role in NYC transportation in 2014.

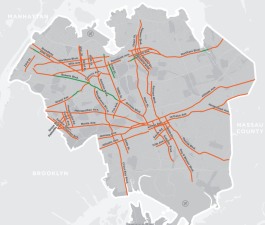

Today, the bicycle lane network densely covers a relatively small proportion of the city with lanes every four to six blocks (as in much of Brooklyn north of Prospect Park today), and protected bike lanes outside of Manhattan or the Brooklyn waterfront are rare. Yet New Yorkers increasingly use bikes to get to transit stations in parts of the boroughs where subway coverage is thin, and people throughout the city travel very short distances for most trips. A five- or ten-fold increase in cycling’s presence on our streets over time would not be out of keeping with other large transit-based cities that treat cycling as a real mode of transportation. For example, recent research puts Berlin’s bike mode share at 13 percent of trips.

Expanding cycling would certainly be consistent with de Blasio’s signature Vision Zero policy. NYC DOT has shown clearly that the traffic calming effects of bike lanes generally, and of protected lanes on city avenues, benefit motorist and pedestrian safety, as well as that of cyclists. Less well known is that no fatal crashes involving cyclists occurred within the Citi Bike service area from May, 2013 when the system began operation, until July of this year, when a (non-Citi Bike) cyclist was killed at a BQE on-ramp along Sands Street.

The de Blasio administration can take advantage of several overlapping policy frameworks to shape its approach to cycling in 2015 and beyond. Framing bike policy through these lenses can produce great benefits for the people of New York and numerous wins for City Hall.

Subsequent parts of this series will examine each of these opportunities in turn: