Meet One of the Minds Behind TrafficStat, NYPD’s Street Safety Initiative

A report laying out Mayor Bill de Blasio’s traffic safety strategy, including a section on policing, is due in less than two weeks. In the meantime, precinct commanders have taken wildly different approaches to the issue, some more successfully than others. As a department-wide traffic safety policy comes into focus, TrafficStat, NYPD’s traffic analysis initiative, is likely to take center stage. Streetsblog spoke with retired Deputy Chief James McShane, who played a central role in the introduction of TrafficStat in the late 1990s.

“It was created because then, like now, there was a spike in fatalities,” McShane said, adding that because records were managed differently in different agencies the city had trouble producing a consistent data set. “That began a dialogue, and a dialogue in the media about how many people were being killed.”

CompStat, which was developed under Police Commissioner Bill Bratton’s command beginning in 1994, was already improving accountability and communication within the department as it tackled violent crime and property crime. Some in the department, led by Chief Michael Scagnelli, thought a similarly rigorous model could have an impact on traffic fatalities. “A determination was made,” McShane said. “Let’s try and take the CompStat model and see if we can apply the philosophy to traffic management.”

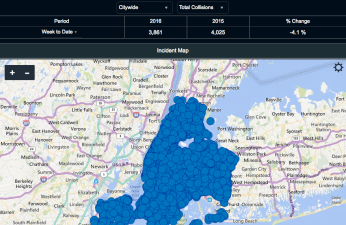

Launched in 1998, TrafficStat developed criteria for identifying crash-prone locations, assigning points based on the severity of injuries and fatalities. Crash investigators came to TrafficStat meetings to explain the contributing factors behind crashes to top brass at the NYPD and DOT. “It became a real-time look at traffic conditions,” McShane said, saying the meetings uncovered a number of factors behind crash-prone locations, from driver recklessness to faulty road design.

Unlike CompStat, TrafficStat involves more than just the police department. “The real innovation is that we brought DOT to the table,” he said. “It became a collaboration.” According to the city, DOT staff including borough commissioners “regularly participate” in weekly TrafficStat meetings, where McShane said they would discuss potential street design changes with police before implementation.

“The meetings are very intense, but it’s critical that everyone realize how serious the department is taking this issue,” Deputy Chief Henry Cronin, commanding officer of the traffic division, told the Daily News in 1998. In the first half of that year, the NYPD issued 32 percent more moving violations than the same period in 1997, before TrafficStat was introduced.

While borough command and top officers from each precinct came to meetings, McShane said it was usually a precinct’s second-in-command, the executive officer, in attendance. Because TrafficStat is within the department’s transportation bureau, it operates on a separate chain of command than the precincts. While the precinct representative would be grilled on his precinct’s traffic safety efforts at TrafficStat, CompStat meetings have tended to be far more high-pressure affairs.

Some police officials are worrying that Bratton’s focus on traffic safety means their feet will be held more closely to the fire. “The word is that [TrafficStat] is going to be much more intense,” one anonymous source told the Post last week.

If Bratton does turn up the heat at TrafficStat, he’ll need a new deputy: Transportation bureau chief James Tuller, who served as transportation chief under Kelly since 2009, left NYPD in November. Bratton has yet to name a replacement.

As for how the city can seriously address traffic violence, McShane has his own views. Unlike the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, which claimed the work should only be done by officers, he thinks automated enforcement can be useful. “You should do both,” he said.

McShane also spoke up for stronger licensing requirements, calling on the state DMV to begin mandatory rules-of-the-road and traffic safety refresher courses for people looking to renew their licenses.

Although Bratton may have a soft spot for jaywalking tickets, McShane, like many within the department, views them more skeptically. “Trying to issue jaywalking summonses in Manhattan is like trying to catch water in your hands,” he said. “I don’t feel, from experience in the nineties, that enforcement against pedestrians will work.”

But McShane, like much of the NYPD, remains focused on ensuring that drivers keep moving, and he isn’t a fan of many of the traffic safety measures DOT has implemented. “One of the goals of TrafficStat — and it used to be the goal of the Department of Transportation — was to ensure the smooth flow of traffic,” he said. “The recent engineering by DOT, I don’t think it’s designed to move traffic. I think it’s designed to inhibit traffic. It’s designed to slow traffic down.”

Instead, he prefers interventions like pedestrian fences at busy intersections, which keep people from crossing at corners. These types of barriers, installed in Midtown by the Giuliani administration, were the target of a cattle-themed protest by Transportation Alternatives in 1997.

Despite the disagreements, McShane enjoyed strong connections with advocates. “I personally had a great relationship with Transportation Alternatives,” he said, adding that officers under his command participated in the group’s NYC Century rides.

McShane was ambivalent about the push to open up more NYPD data about crashes and investigations to the public. “Everybody wants more data. This is a data-driven world,” he said, but he noted that things have gotten harder for advocates in the recent years. TrafficStat continued under former Commissioner Kelly, but advocates say they have less access to it now than they did before. “The police department became less transparent under Ray Kelly,” McShane said.