Congestion Charging in New York City: The Political Bloodbath

Though many New Yorkers are learning about congestion charging for the first time this week, the transportation policy community has been working to sell this idea to a resistant public for more than three decades. What happens when Nobel Prize winning theory meets bare-fisted New York City politics? A heavily condensed version of this story ran in this week’s New York Magazine:

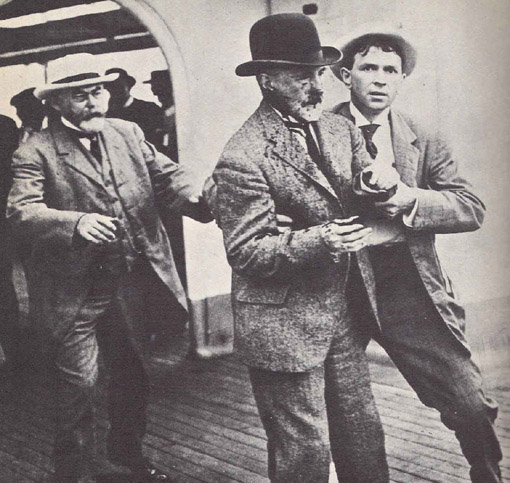

Mayor William Jay Gaynor, August 9, 1910, moments after being shot in the throat by a disgruntled former City employee. On the left, moving forward to help the mayor is Robert Todd Lincoln, the only surviving son of the first U.S. president to be assassinated. (Photo: William Warnecke)

Perhaps New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg was channeling the ghost of one of his predecessors, Mayor William Jay Gaynor when he dismissed the possibility of London-style congestion charging as "a non-starter" the other day.

Gaynor was Mayor of New York City nearly a century ago. Like Bloomberg, he was a political outsider, never even having set foot in City Hall until the day of his inauguration. Like the current Mayor, Gaynor was also a kind of technocratic managerial type. Rather than appointing hacks and cronies from the Democratic Party machine of Tammany Hall, he was noted for filling his administration with competent civil servants.

Perhaps not as good at negotiating city contracts as Bloomberg, on August 9, 1910, Gaynor was shot in the throat by a disgruntled former city employee. The Mayor survived the assassination attempt and a few months later removed the five cent tolls from the four bridges crossing the East River. The bridges have been free ever since, doomed to a century-long cycle of disrepair followed by expensive emergency fix-ups.

While "there’s never been a serious connection drawn between the assassination attempt and Gaynor’s tolling policy," says former Department of Transportation Deputy Commissioner "Gridlock" Sam Schwartz, "I’m suspicious."

Schwartz has reason to be suspicious. He is one of a small cadre of transportation policy experts who have been working, in some cases, for more than thirty years to sell the idea of congestion charging to a resistant public and political power structure. The idea of using pricing to control the amount of traffic that flows into Manhattan has a long bitter history and you can hear it in the voices of those who have worked on the issue the longest.

In 1973 Mayor John Lindsay, Governor Nelson Rockefeller approved a plan to bring New York City into compliance with the federal Clean Air Act by putting .50 cent tolls on the East and Harlem River bridges. In those days before unleaded gas and catalytic converters, the plan was to clean up the city’s air by simultaneously reducing motor vehicle traffic and raising money for the failing transit system. Brian Ketcham was a young, rising star in the Lindsay Administration, responsible for developing the city’s clean air plan and selling it the public.

"The taxi industry hated me. The trucking industry, at that time mafia-controlled, was threatening me. Everybody was angry. It was a lot of agony." he recalls. "Eventually, the business community and government decided they didn’t want tolls. They finally fired me because I was trying to get it enforced and they were trying to bury it," Ketcham says.

The National Resources Defense Council sued the city and in 1975 the federal government moved to enforce the plan. Finally, in 1977, Senator Daniel Moynihan and Representative Elizabeth Holtzman amended the federal Clean Air Act to allow New York City to forgo tolls in return for funding the transit system through other sources. "That really, ultimately led to $40 billion of investment and the saving of the transit system," Ketcham says.

Upon leaving government, Ketcham and his wife, Carolyn Conheim, also in the Lindsay Administration, set up shop as consultants and continued to advocate for bridge tolls. "I pursued it for about 15 years in a tortured effort but I finally gave up on it. There’s only so much of your life you can devote to that kind of crap until you just say, ‘Well I’ve done as much as I could.’"

"The fact of life," Ketcham admits, "is that back in ’77, we still didn’t have the technology to do it. Accommodating toll plazas on the bridge entrances and exits was clearly an impossibility. But it led to saving the subway system. It was, you know…" Ketcham’s voice trails off. "I suffered a lot and it cost me a shitload of money. But in the end the public benefited."

"Gridlock" Sam worked with Ketcham during the Lindsay administration and later became a Deputy Commissioner for the Department of Transportation under Mayor Ed Koch. "In 1980 after the transit strike, Ed Koch actually introduced a traffic regulation, a new law, to charge people in driver-only cars. If you wanted to drive into Manhattan and you were alone in your car you had to use one of the toll facilities," Schwartz said.

The legislation passed City Council and was within days of being implemented when the parking garage industry and the Automobile Club of New York sued to stop it. "We lost the law suit on the argument that the city didn’t have the authority to toll the bridges. Tolling the bridges requires state legislation." Though many of today’s congestion pricing advocates believe Automobile Club of New York v. Koch is flawed and could be overturned in court (PDF file), the City’s own lawyers and many in Albany believe that any congestion pricing system that involves tolling the city’s bridges must go through the state legislature before its enacted — an added complication to say the least.

Schwartz who later became renowned for inventing the term "gridlock," for posting signs in midtown reading, "Don’t even think of parking here," and for having Mayor Koch’s car ticketed for illegal parking while the two were having lunch together, has been advocating a complete redesign of New York City’s tolling system for years.

"We really have a very dysfunctional pricing scheme in New York City," Schwartz says. He blames much of the dysfunction on Republican Senator Alfonse D’Amato who in 1986 used federal law to get rid of the eastbound tolls on the Verrazano Bridge as a gift to his Staten Island constituents. The one-way toll, according to Schwartz is one of the most "pro-congestion" traffic measures ever enacted in New York City. It "encourages truckers to barrel down the rickety BQE and downtown Brooklyn’s neighborhood streets, bounce across the creaky Manhattan Bridge, thunder over choked Canal Street, and leave the city via the Holland Tunnel" which is also free going westbound. Using this circuitous route, New Jersey and Staten Island truckers and commuters can save as much as $40 a day in tolls. Neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Lower Manhattan bear most of those costs instead.

Schwartz believes that where motorists don’t have good mass transit options and where tolls don’t do much to reduce traffic in the city’s central business districts, they should simply be eliminated. The tolls on the Whitestone, Cross Bay and Marine Parkway bridges in Queens are good examples.

In fact, "we shouldn’t even be thinking in terms of ‘tolls’ anymore. We should be thinking in terms of 2010 technology" that will allow us to charge variable fees based on traffic conditions, time of day or the kind of car you’re driving, he says. "We may not have a problem with someone coming over the Brooklyn Bridge on their way to the Bronx and staying on the FDR Drive. But if they want to drive up First Avenue to bypass some of the traffic, we’re going to charge them money. If you want to drive by and show your kids the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree from the window of your SUV, I’ll charge you $25 for the pleasure of doing that. We should use pricing to establish traffic patterns that are desirable."

Schwartz gave congestion charging one more shot before he left city government. In 1987 "DOT commissioner Ross Sandler and I got Koch to go forward and propose congestion pricing," Schwartz recalls. The result? "There were demonstrations in front of City Hall. We were nearly tarred and feathered."

Ethan Geto was the political operative handing out the tar and feathers. Geto’s playbook for killing the Koch proposal is classic bare-fisted New York City politics and gives you a good sense of what any traffic reduction proposal is up against, even today. "I forged a business-labor coalition," Geto says. "At the time, the number one labor leader in the city was a guy named Barry Feinstein, president of the Teamsters. The Teamsters repped the parking garage workers. It was so fucking parochial."

With Big Labor on board, Geto rounded up the Borough Presidents, the tourism, hotel and entertainment industries, and found that hospitals also wanted to keep it cheap and easy for their patients and doctors to drive into Manhattan. "Then we got Lou Rudin, the city’s number one business and civic leader as president of the Real Estate Board of New York. It was a real powerhouse group. We had a meeting — just three guys in the room. Rudin and Feinstein conveyed the message to the Mayor. Koch withdrew it." And that was that.

Undeterred by previous failures, the Dinkins administration made a move towards congestion pricing as well. In 1990, Janette Sadik-Khan, Mayor Dinkins’ Transportation Advisor, had just completed the first draft of a major study on East River Bridge tolls.

"I remember walking into Assembly Speaker Mel Miller’s office. He was the first guy that I was presenting the results of our study to and I said, ‘Hi, I’m here from New York City DOT to talk to you about the proposal to toll the East River bridges," Sadik-Khan recalls. "He looked at me and gave me this big smile and said, ‘Oh, that’s so cute!’"

"That pretty much epitomized the uphill battle that we faced politically at the time."

Today Sadik-Khan is a vice president at Parsons Brinkerhoff, a global engineering firm that specializes in large-scale transportation projects. She and her staff are leading participants in the traffic congestion study that the Partnership for New York City released today (PDF). Fifteen years after her Mel Miller experience she says, "I’m not sure that the politics have changed that much. There tends to be a knee jerk reaction to anything associated with pricing."

When the issue of congestion pricing was raised in the immediate aftermath of Bloomberg’s landslide victory, the mayor killed it just about as fast as he possibly could. The idea was floated on the front page of the New York Times, above the fold, in a quote by Partnership for New York City president Kathy Wylde. Immediately, the idea of a congestion pricing push during Bloomberg’s second term swallowed up the news cycle. Cornered by reporters on Fifth Avenue before the start of the annual Veteran’s Day parade, a clearly annoyed mayor slapped the idea aside, saying, "It’s not on our agenda to look at it." And just like that, congestion charging was dead again.

Geto, for his part, says that his successful effort to kill traffic reduction during the Koch Administration is the one major lobbying campaign in his career that really gives him reservations. "Traffic has reached such a point that it is clearly a net negative for the city’s economy."

But his experience running another controversial public policy effort, the city’s 1995 and 2002 ban on smoking in restaurants and bars, gives him the sense that if Mayor Bloomberg really wanted to take major steps to reduce traffic congestion in New York City he could do make it happen. "Every lobbyist in the city was working for Phillip Morris. We stitched together a public health coalition with much less funding. Everyone said, ‘You’ll never get this done.’ All the doom and gloom turned out to be scare tactics by people with very parochial interests."

While Geto acknowledges that the traffic issue is more complex than smoking, which had three decades of public health studies and national campaigning behind it before the city’s ban went into effect, he believes that with the city’s business groups, civic associations and public health community all clamoring for traffic relief, the time is right for another run at congestion pricing.

But how do you sell it to a resistent public via a reactionary tabloid media? "It’s always the substance that sells it. You’re not going to sell this through bullshit public relations." To sell congestion pricing, Geto says "you’d have to create a variety of incentives to coax people out of their cars and improve other transportation options. You’d have to ease the pain for certain constituencies and make people in Brooklyn and Queens happy. You’d need to put together a package that says, ‘Look, we’ve got to bite the bullet on something that’s very tough for this town but the pay-off is going to be enormous.’"

"No matter how you slice it you’re going to have people squawking. It’s going to be a fight. But Bloomberg took on smoking. He reorganized the schools," Geto says. "There are very few things that a mayor can do that would have the kind of impact that a traffic reduction program could have on improving quality of life in this city."

"Talk about a Bloomberg legacy – this would be it."